alumni Connections alumni Connections

Patients with rare disease turn to EVMS grad now at NIH

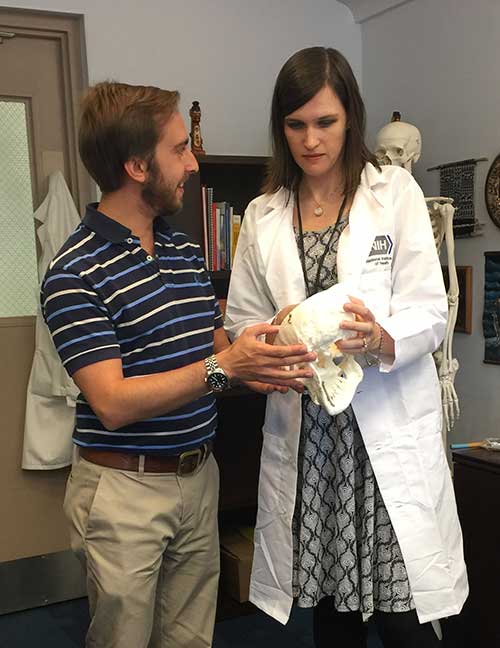

Though rare diseases affect just a small part of the population, Alison Boyce, MD (MD ’06), says researching them can lead to advances in medical science that will benefit everyone.

“Research in rare diseases teaches us a lot about biology and medicine in general,” says Dr. Boyce, a pediatric endocrinologist and research physician with the NIH Section on Skeletal Disorders and Mineral Homeostasis. “Most rare diseases result from a single gene mutation. Understanding how and why these mutations cause diseases can give us valuable information about biological pathways in the body and increase our understanding of normal physiology.”

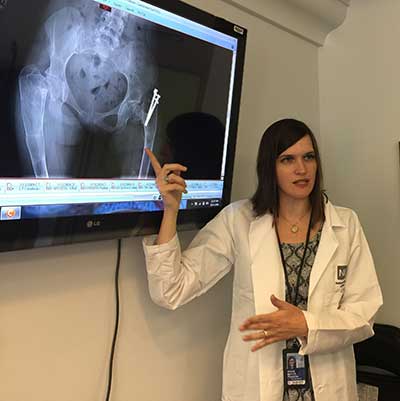

Much of Dr. Boyce’s work is focused on fibrous dysplasia/McCune-Albright syndrome (FD/MAS), a rare bone disorder typically diagnosed in early childhood. Hopeful for treatments to minimize its pain and debilitating effects, patients with the disease come from all over the world to see Dr. Boyce and her colleagues at the NIH Clinical Center. Dr. Boyce is the principal investigator on a natural history study for FD/MAS and is helping to plan a clinical trial to test the drug denosumab on adults. She also trains other healthcare providers — particularly pediatricians — to identify symptoms in very young children. Caused by a genetic mutation, the condition affects skin pigmentation, hormone production and bone growth. There is no cure.

“It’s a tricky disease [to diagnose],” she says, “but there’s really an opportunity to treat it effectively if you can identify very early the kids who are affected.”

Dr. Boyce is grateful to EVMS for enabling her to meet her husband, Peter Tait, MD (MD ’04), now a hospitalist in Washington, D.C., and for the school’s emphasis on clinical experiences and community service. Today, she volunteers as a clinician in the Bone Health Clinic at Children’s National Health System and works with the Fibrous Dysplasia Foundation and the MAGIC Foundation.

“EVMS was really essential in preparing me to be a good clinician and to approach the patient as a whole person,” Dr. Boyce says. “Every time I see and counsel a patient with a rare disease, it makes the case that we desperately need better ways to diagnose and treat them. We’re most likely to make progress when researchers are closely connected to the patients and families affected by the diseases we study.”